SMEconomics Overview

-

The delta lockdowns across the south-east of Australia have been a major setback for Australia’s economy. The pandemic recovery has rapidly been transformed from a vigorous V-shape to a disappointing W.

-

Despite 10% plus falls in economic activity in NSW and Victoria in the middle of 2021, there is light at the end of tunnel. Australia’s belated COVID-19 vaccination rollout has been a success with government targets looking likely to be achieved ahead of the original timelines. This should pave the way for a strong recovery in economic activity in late 2021 and 2022.

-

NSW and Victoria have been most severely impacted by the delta wave. Hours worked in NSW, a proxy for economic activity, fell 13% from June to August – the largest fall since the survey began in 1978, and almost 4 times the magnitude of the decline in economic activity through the early 1990s recession.

-

Government policy support has been swift and seemingly effective in these latest lockdowns. Not only has monetary policy remained exceptionally expansionary, but state and federal government income support programs for households and businesses have been put in place quickly.

-

It is a long way back for both Victoria and NSW. The NSW and Victorian economies have the greatest potential to grow after lockdowns drove big declines in economic activity over the second half of 2021. To get the NSW economy back onto its pre‑pandemic growth path, activity will need to rise by between 15 and 20%, which could take a year or more.

-

The states that have avoided major outbreaks of delta have fared much better and are likely to continue to grow right through 2022. Income support programs, tax incentives and low interest rates are supporting investment across the economy despite the on-going pandemic. Non-mining business investment is rising, as is construction activity. Property prices are rising across the country.

-

Unemployment has fallen to 12 year lows despite the delta outbreak. Australia’s unemployment rate hit 4.5% in August despite a big drop in employment. Federal government income support programs are supporting temporarily displaced workers, which is ensuring consumer confidence holds up. Business confidence has fallen from record high levels before the delta outbreaks but is holding above recession levels.

-

The international environment has become more challenging on a range of fronts. Previously buoyant iron ore markets have seen large price falls in July, August, September which will reduce national income. Supply chains remain stretched with import costs rising and deliveries coming through more slowly than usual. Global economic activity has slowed from the buoyant pace of the first half of 2021.

-

Financial markets continue to perform well with long term interest rates near historical lows and equity market valuations are at extraordinarily high levels. Despite these high valuations the market has seen very little volatility in 2021, other than the volatility of constant price increases. Markets will continue to be supported by low interest rates. The main vulnerability will come from weaker economic growth. The global economic outlook remains positive for 2022. Geo-political risks appear to be the most worrisome element of the outlook.

First Look: Australia's economy 2022

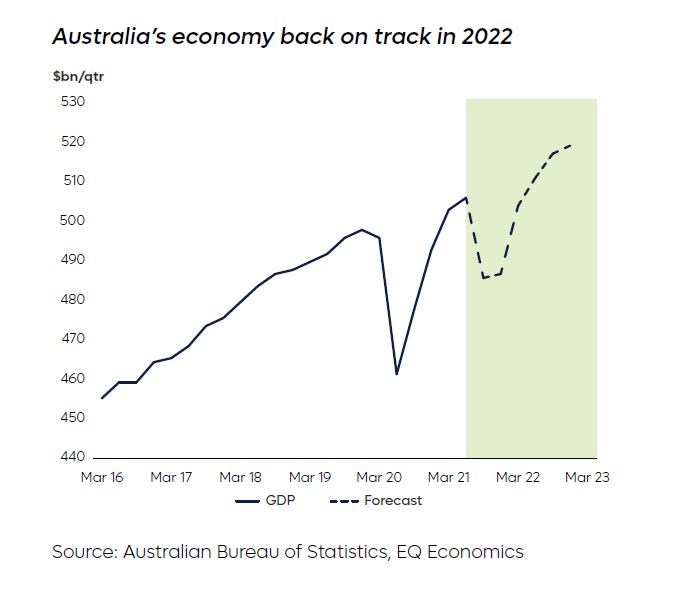

Australia is set for a strong economic rebound in 2022 as vaccination targets are achieved and domestic and international borders are re‑opened. The downturn in economic activity over the second half of 2021 will provide a low base from which the economy can grow as restrictions on mobility are eased. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) could surpass $2trn in 2022, a 3.5% lift on 2021 and the highest level of economic output on record.

The NSW and Victorian economies have the greatest potential to grow after lockdowns drove big declines in economic activity over the second half of 2021. Queensland also appears to have been impacted, despite an absence of extended lockdowns. Queensland was charging ahead of all other states until the delta lockdowns in NSW and Victoria created problems for parts of its economy.

The surprise of the delta lockdowns of 2021 has been the performance of the South Australian and Western Australian economies. The lockdowns reducing economic activity in the south-eastern states have been but the lightest of headwinds to South Australia and Western Australia. Both state economies continued to grow through the delta outbreaks and are well positioned to expend activity as the national economy opens in 2022.

Beyond the expected bounce in economic activity due to an easing of restrictions, there are other good reasons to believe the economy can perform well in 2022. Stimulus has effectively been ‘stored’ in the system through household and corporate savings. The monetary and fiscal stimulus that has been injected into the economy since the beginning of the pandemic will continue to support consumption and investment over the years ahead.

Australian households have accumulated savings at the fastest pace in decades, much of which has been the result of the inability to spend current income due to restrictions on economic activity. At the very least this money will be a buffer should future challenges emerge. In all likelihood, this money will be deployed into the economy as we open up.

Monetary policy remains very easy even if further interest rate reductions or quantitative easing are unlikely. The RBA continue to signal that interest rates will remain at current low levels well beyond 2022. Low rates encourage investment and support house prices.

As the accompanying chart highlights, the economic recovery from the delta lockdowns will take time to materialise, but when it does, the expectation is for a return to pre-lockdown levels of national economic activity by the middle of 2022.

A strong economy will bring with it challenges for business, many of which are already evident in 2021. The most pressing problem for many organisations will be retaining and attracting staff. With virtually no immigration at present, Australian businesses will need to source new staff from the domestic pool of labour or come with innovative capital and technology solutions to alleviate labour shortages.

While this may drive a new wave of productivity enhancing investment, it will be a challenging environment for many businesses. Australia’s economy back on track in

Consumers have built up a war chest of savings

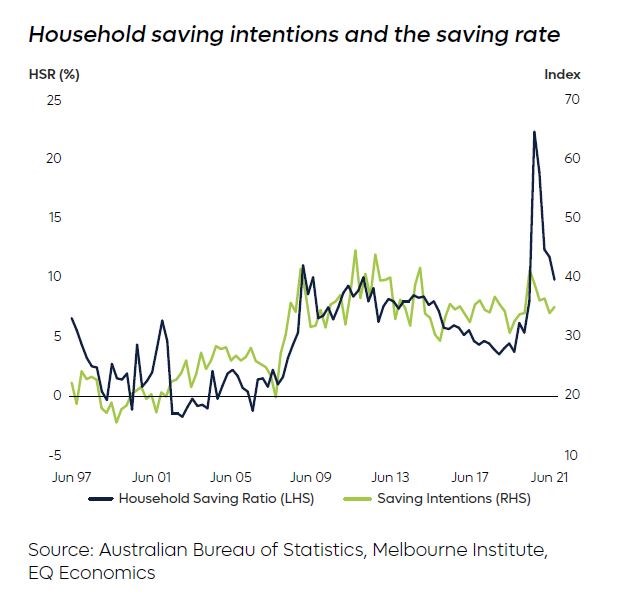

Consumer savings have surged through the pandemic. According to ABS data, new household savings over the 18 months to June 2021 were $253bn. Prior to the pandemic households were saving about $50bn a year. This suggests that there has been a substantial amount of excess savings that have accumulated through the course of the pandemic.

Why has the saving rate surged in the last 18 months?

-

- Greater economic uncertainty will tend to see an increase in savings. These savings may not be spent if consumers continue to feel the need to hold financial buffers against future uncertainty.

-

- Restrictions on consumer spending due to public health orders. This is the component of savings that reflects the inability of consumers to spend and, presumably, will be available to spend once restrictions ease.

The trick is to work out what the desired level of saving has been through the pandemic. Some of the total new savings during the pandemic would have happened even in the absence of a pandemic. It must also be considered that the pandemic has changed consumer attitudes to saving, resulting in an increased desired saving rate due to uncertainty.

Using consumer attitudes to saving contained in the Melbourne Institute consumer sentiment survey, an estimate for ‘desired’ savings can be made. This analysis shows that the uncertainty of the past 18 months has resulted in a higher desired rate of saving by Australian consumers, but this in no way matches up with surge in actual saving. The implication is that restrictions have stopped consumers from spending on certain items and, rather than spend the money elsewhere, or invest it, the money is sitting in bank accounts.

In the five years prior to the pandemic the household saving rate averaged about 5% of disposable income. The saving intention estimate suggests that the desired saving rate spiked to about 10% at the onset of the pandemic, and has since fallen back to around 7% in 2021, still below the current household saving rate of 9.8%.

Clearly the uncertainty and disruption induced by the pandemic has resulted in a higher targeted rate of saving by Australian consumers. However, restrictions on mobility and ability to spend on services has meant that savings have risen even higher than the targeted rate. The difference between actual savings and targeted savings could be viewed as excess saving. This excess saving could be considered the money that is available for consumer to spend once restrictions ease, over and above future income.

On these estimates households have accumulated $125bn of excess savings over the 18 months to June 2021. With lockdowns extending through the second half of 2021, and based on the current household saving rate, it is likely that this number will rise to around $160bn. That is $160bn of potential spending that could supplement household income.

In 2019 household consumption topped $1trn. Consumer spending typically grows by around 3.5% each year. This $160bn of excess saving represents about 15% of annual consumption in Australia. This has the potential to provide a major boost to consumption as we exit the pandemic and normalise economic activity.

What is clear is that this money will either be a meaningful support to household incomes or a major boost to consumer spending over the next two years. Either way, it is a strong rationale for holding an optimistic view of demand conditions in the Australian economy right through to 2023.

How will consumers be spending their money in 2022?

In 2022 Australian consumers should be in a strong financial position. The demand for labour should ensure that employment will grow. A potential shortage of workers should ensure that incomes will grow. As outlined in the previous article, the massive accumulation of savings by Australian households since the pandemic began should ensure that spending grows at an even faster pace than both employment and income.

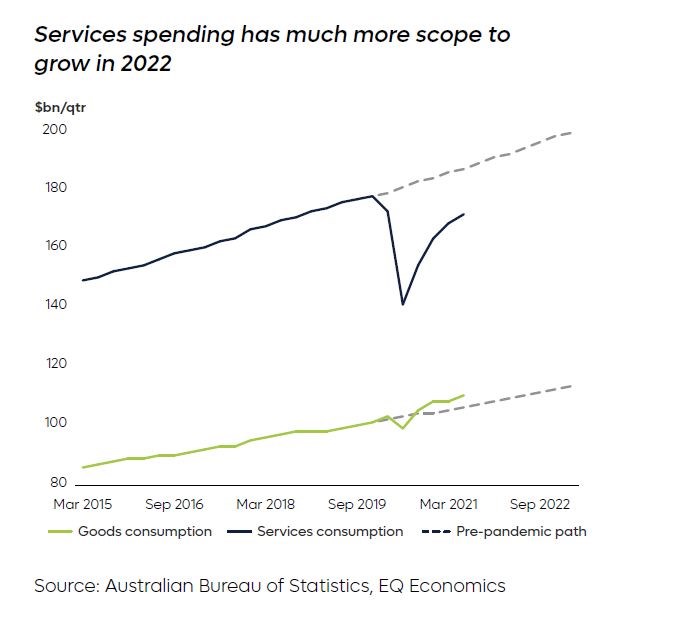

The big shift in consumer spending through the course of the pandemic has been away from services towards goods. As displayed in the accompanying chart, consumer spending on goods has grown at a faster pace than what we saw prior to the pandemic.

Goods spending generally accounts for just over one third of consumer spending, amounting to just under $400bn in 2019. Services make up the bulk of consumer spending, about $700bn in 2019. Public health orders have been a major obstacle to consumer spending on services, mostly discretionary services related to hospitality and recreation. Services spending fell 10% in 2020 compared to 2019. Goods spending continued to grow.

Over the first 18 months of the pandemic (to June 2021) goods spending has broadly maintained the pre-pandemic path, a little higher if anything. The same cannot be said for services spend. Based on the pre-pandemic path, over the past 18 months services spending has been $125bn less than it otherwise would have been.

These trends will remain in pace over the second half of 2021 as lockdowns in the large states and restrictions on interstate travel continue right through into the final quarter of the year.

As Australia’s vaccination rate rises and the economy opens up, we are likely to see a major realignment of consumer spending in 2022 and 2023. Some analysts are concerned that we may see a slump in spending on goods as pent‑up demand for discretionary services, particularly holidays, absorbs the discretionary consumer dollar.

There is little doubt that services spending should surge in 2022, partly due to pent up demand, but largely because of a normalisation of spending patterns. Importantly, the outlook for consumer spending on goods remains strong despite the solid pace seen right through the pandemic.

The large accumulation of excess savings will be an important driver of strength in consumer spending on both services and goods. Critically, we are experiencing a major upswing in housing demand and residential construction. This will invariably support consumer spending on household goods as people move into new dwellings, both established and newly constructed.

The uncertainty for 2022 is not whether consumer spending will be strong or weak. The issue is which segments will be super strong and which will experience normal demand conditions. It is hard to see significant weakness in consumer spending outside of very specific sectors that have benefited from the restrictions placed upon the economy.

If services spending gets back to its prepandemic path in 2022 then we would expect to see a 14% increase in services spending in 2022 compared to 2021. This translates into an extra $100bn of spending on services in 2022 compared to 2021. The biggest growth opportunity is likely to be seen in those sectors that have been subject

Labour costs in the RBA's targets

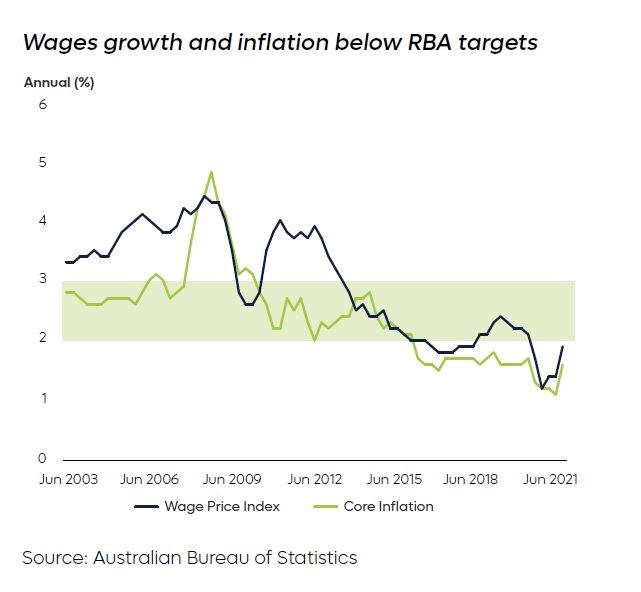

The RBA Governor Philip Lowe has spelled out the monetary policy strategy with candour and clarity in a recent speech. The RBA remains squarely focused on getting CPI inflation within its 2% to 3% target range and by doing so, driving unemployment as low as possible.

For the RBA, monetary policy has a sole purpose, and that is to maintain inflation between 2% and 3%. Underlying inflation has been running below the target range for the past five years. Although we saw a spike in the inflation numbers to June of this year, this was the result of one-off factors that will almost immediately be reversed. The current underlying trend is still below 2%. The RBA is desperate to get inflation above 2% after half a decade of missing their target.

Low inflation has been a global phenomenon, but with Australia having a higher inflation target than other advanced economies, the problem of ‘undershooting’ our inflation target appears to be much worse here. The RBA appears to be feeling considerable pressure to achieve its target.

The only way to get inflation permanently higher is to get business costs rising on an on-going basis, which forces them to raise the price of their products to maintain profit margins. In most countries this means getting wage growth higher because wages are the largest cost that most organisations face.

The problem is that wage growth has been soft in the past 10 years, particularly in Australia. The RBA wants to change all of that. The Governor has made it very clear that to get inflation above 2%, we will need to see wages rise by more than 3% per year.

How do you get wages growth up? One way is for productive firms to pay higher wages because they are more profitable. The benefits of profitability are shared between the owners (dividends) and the staff (wages). There is plenty of evidence across many economies of the strong relationship between wages and productivity in an economy.

The Problem for Australia, and many other countries, is that productivity has been noticeably absent in the last 10 years and, with it, wages growth. In any case, there is little the RBA can do about productivity. Monetary policy can ensure a stable economic and financial environment for businesses and households to operate, but it cannot make workers produce more output for each hour of time they spend on the job.

What the RBA can do is drive demand in the economy through accommodative monetary policy, which in turn increases the demand for workers. If they can push hard enough, they can produce an environment of excess demand for staff. If there are more job vacancies than people to fill them, employers will need to pay more to retain and attract staff - which leads to wage growth.

This is the RBA’s clear intent which, during a once in a century global pandemic, looks very likely to succeed given constraints on the supply of labour due to the closed international border.

For Australian businesses the implication is clear, if not already evident: retaining and attracting staff is going to be more important than ever over the year ahead.

Labour shortages to persist well into 2022

The desire of policymakers to drive higher inflation in Australia via higher wage growth is likely to create a highly challenging environment for business. The unique circumstances that Australia finds itself in with a closed international border because of the pandemic makes a high demand for labour in the economy more difficult.

The evidence from the first 18 months of the pandemic shows how much of a problem finding new staff already is, and until we resume a normal flow of immigration, both temporary and permanent, the situation will only get worse. All signs are that the demand for labour across the Australian economy will only increase over the year ahead if the economy resumes the strong recovery path after the delta lockdowns of 2021.

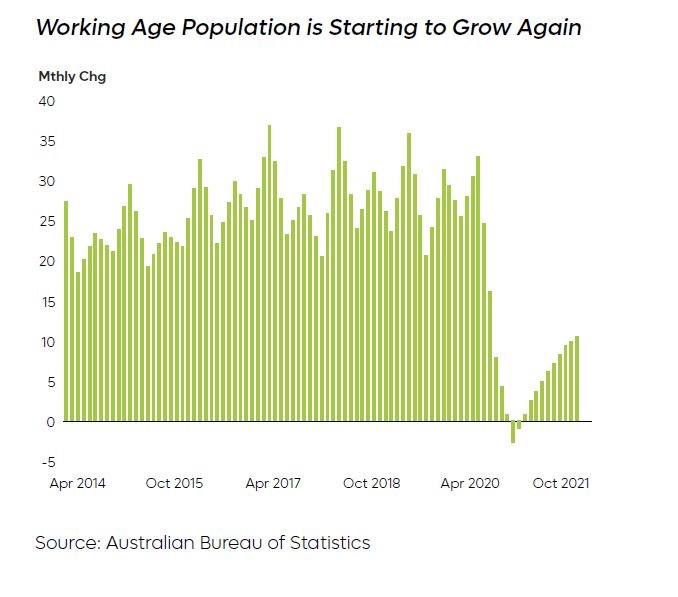

Closing the international border to new migrants has meant that the supply of new workers into the economy has slowed right down over the last 18 months. The chart shows estimates for the monthly growth in the working age population over the last 6 years.

Since the pandemic began working age population growth has fallen from 25,000 a month to 5,000 a month. Population growth is starting to rise back to a level in line with the natural (domestic) increase at 11,000 a month in the middle of 2021. There has been some allowance for workers to come into Australia in the pandemic, but the numbers are not big enough to have a meaningful impact on the aggregate data.

Until the international border is open, and the normal flow of temporary and permanent visa holders is re-established, the supply of workers into the Australia economy will be running at less than half the ‘normal’ pace.

All indications are that the demand for labour across the Australian economy is as high as it has ever been. Indeed, measures of job advertising and vacancies are at the highest level on record. This is partly because of a loss of temporary visa holders, but is also a genuine desire on the part of organisations to expand.

Estimating labour demand from these indicators suggests that in 2022 we will need upwards of 30,000 new workers a month. This pace is significantly above the expected growth of working age population and, until borders are opened, will make life difficult for employers.

Clearly the desire of the RBA is for this scarcity of labour to result in an increase in wages. This is starting to happen in certain sectors. For some businesses these labour market dynamics could mean that they will not be able to expand or, worse still, they may have to shrink operations if exiting staff cannot be replaced by new staff.

How this plays out is hard to know. It is likely we will see a mix of outcomes. In many cases wages will rise at a much higher rate than in recent years. In other cases organisations will find technology solutions to labour shortages. Unfortunately, there will also be cases of businesses shrinking.

For the RBA, the objective to get higher wages looks like being met. The big question is whether business will be able to put up the price of their final products to offset the increased costs. That is one of the major uncertainties facing the economy in 2022 and how it is resolved will determine what happens

Interest rate outlook

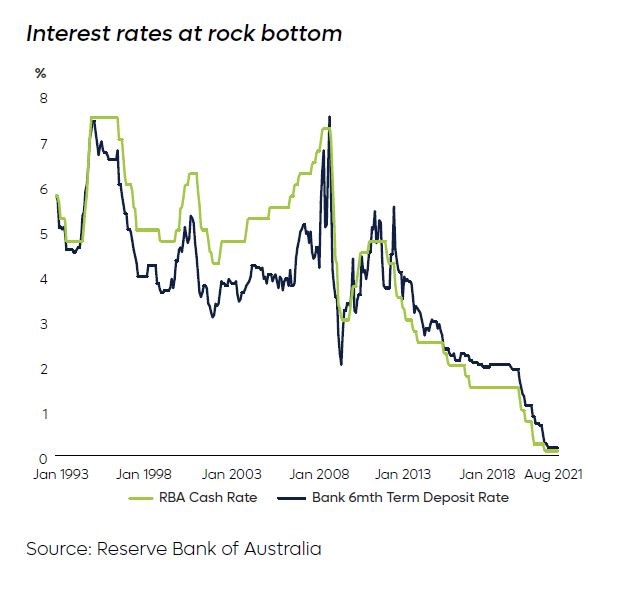

Interest rates are determined by a combination of local and global factors. The anchor for all interest rates in Australia is the RBA cash rate, as set by the RBA Board at their monthly meeting. As recently as September 2021 the RBA Governor has made it quite clear that they do not expect to be increasing rates before 2024. They are determined to keep interest rates low until inflation rises consistently into their target band of 2%-3%. In 2021 both wages and inflation remain low and well below the growth rates the RBA requires to trigger a rise in interest rates.

This seems at odds with the experience of business and what we are seeing in overseas markets. Material shortages, rising shipping costs and emerging shortages of staff are putting upward pressure on business costs. These local and global cost pressures are very real, mainly the result of supply shortages caused by the global pandemic, and could result in higher consumer prices over the year or two ahead.

But these cost pressures are different to inflationary pressures. Inflationary pressures come from a combination of concerns about higher prices for everyday goods and services (inflation expectations) and those concerns being successfully translated into higher wage outcomes. It is a self-reinforcing cycle of higher wage costs and higher consumer prices that generates permanently higher inflation.

If anything, the self-reinforcing cycle has worked in the opposite direction over the last 20 years, with competition, technology and better business practises pushing down the price of goods and services in the economy. With low inflation entrenched and people concerned as much about job security as higher wages, workers have tended to hold off on higher wage claims.

Even if inflation starts to rise above the RBA target over the next few years, interest rates will not have to rise by very much to have a big impact on economic activity and quell any inflation pressures. Over the last three decades, as interest rates have declined, the quantum of debt held by governments, business and households has increased to levels we have never seen before.

In Australia much of this debt is in the form of mortgages held by households at variable interest rates. When interest rates rise, so to do mortgage repayments. A relatively small increase in short-term interest rates will have a powerful impact on household finances and hence the economy.

This all but guarantees interest rates will not rise by much, but also that interest rates will likely come down once again.

According to the RBA we are set for an extended period of very low interest rates. All around the world interest rates are at historic lows. Economies have become reliant on low rates, and the adjustment to higher rates is often a painful one that can be harmful to the economy.

If the RBA is right, we will not need to worry about the impact of higher rates for many years to come.

Disclaimer

This document has been prepared by Judo Bank Pty Ltd ABN 11 615 995 581 AFSL 501091 (“Judo Bank”). Any advice contained in this document has been prepared without taking into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on any advice in this document, Judo Bank recommends that you consider whether the advice is appropriate for your circumstances.

So far as laws and regulatory requirements permit, Judo Bank, its related companies, associated entities and any officer, employee, agent, adviser or contractor thereof (the “Judo Bank Group”) does not warrant or represent that the information, recommendations, opinions or conclusions contained in this document (“Information”) is accurate, reliable, complete or current. The Information is indicative and prepared for information purposes only and does not purport to contain all matters relevant to any particular investment or financial instrument. The Information is not intended to be relied upon and in all cases anyone proposing to use the Information should independently verify and check its accuracy, completeness, reliability and suitability and obtain appropriate professional advice. The Information is not intended to create any legal or fiduciary relationship and nothing contained in this document will be considered an invitation to engage in business, a recommendation, guidance, invitation, inducement, proposal, advice or solicitation to provide investment, financial or banking services or an invitation to engage in business or invest, buy, sell or deal in any securities or other financial instruments.

The Information is subject to change without notice, but the Judo Bank Group shall not be under any duty to update or correct it. All statements as to future matters are not guaranteed to be accurate and any statements as to past performance do not represent future performance.

Subject to any terms implied by law and which cannot be excluded, the Judo Bank Group shall not be liable for any errors, omissions, defects or misrepresentations in the Information (including by reasons of negligence, negligent misstatement or otherwise) or for any loss or damage (whether direct or indirect) suffered by persons who use or rely on the Information. If any law prohibits the exclusion of such liability, the Judo Bank Group limits its liability to the re-supply of the Information, provided that such limitation is permitted by law and is fair and reasonable.

This document is intended only for clients of the Judo Bank Group, and brokers who refer customers to the Judo Bank Group, and may not be reproduced or distributed without the consent of Judo Bank.

The Information is governed by, and is to be construed in accordance with, the laws in force in the State of Victoria, Australia.