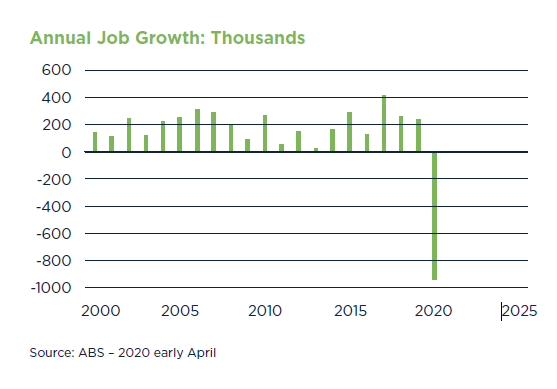

This is serious. When will it end? Where will it end? In early May, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released data suggesting that almost 1,000,000 people had lost their jobs since mid March 2020.

For context, each month, job growth figures go up or down around 20,000. That’s normal. In the full year of 2019, just over 250,000 jobs were created and in 2018, the number was 270,000.

The job losses from March/April this year are simply staggering. As the Governor of the Reserve Bank and others have said, we have not seen losses of this magnitude since the Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Question:

Are we headed for another Great Depression or did we heed the lessons of our past?

Have we learnt anything from the recessions of 1970s, 1980s and 1990s? None were pleasant. All saw significant business failures, job losses and social trauma.

The short answer is that we are unlikely to slip into depression, where the unemployment rate exceeds 20%, and yes, we have learnt something from the mistakes of the past.

The Australian economy was vastly different in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Indeed, there are three critical factors fundamental to the Depression era’s economic reality, that are NOT present in our reality today.

During the Great Depression, interest rates were pushed higher, banks cut back lending and governments cut spending. In today’s terms we would summarise the Depression era government response as; tighten monetary policy, induce a credit squeeze and adopt austerity measures. History shows us that those policies made matters worse and extended the misery.

What have we learnt?

Interest rates in the Great Depression rose because Australia and other nations had fixed exchange rates. Fixed exchange rates were based on the Gold Standard, a system that was thought to be stable and would discourage inflation. This system simply did not work in a growing world economy.

To defend the currency or to keep the currency at its fixed rate, interest rates in Australia had to rise. Back then, we had the Australian pound and it was tied to the UK pound sterling.

Lesson Learnt #1:

Interest rates

The first lesson was that Australia needed to control its own interest rates. To do that we needed to abandon a fixed exchange rate. The Australian dollar was floated in December 1983. Since then, Australia has been able to set short term interest rates according to the needs of the economy, rather than the needs of defending the currency.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) was established in 1959 and makes its decisions on interest rates independently from the government of the day. Politicians no longer take the blame for rising interest rates or the praise when they fall.

Unlike the Great Depression, interest rates in Australia have fallen to record lows and will remain that way for several years. This eases the burden on business borrowers, helps them retain employees and will help in preventing an economic depression.

As a bonus, the exchange rate has fallen, making our exports more competitive and raising our income from foreign earnings. Unfortunately, this does raise the price on imported business equipment.

Lesson Learnt #2:

Government spending

During the Great Depression, State governments wielded the greatest economic power. They were advised by the visiting governor of the Bank of England to pursue balanced budgets.

Given the decline in tax revenue from trade, State governments cut spending or, as we would say today, they introduced ‘austerity measures’. This proved disastrous for the Australian economy and extended the length of the depression.

Today we have the exact opposite. In a matter of weeks, the Federal government has committed to spending around $350 billion to support economic activity. This is mostly in the form of the JobKeeper and JobSeeker programs. Other spending programs have focussed on assisting business cash flows.

While these programs are unlikely to prevent a recession, they will most likely save us from another Great Depression. It is impossible to predict with any level of certainty exactly what will unfold. However, in considering the explanations above, we can safely adopt a stance of cautious optimism regarding our economic recovery. What we do know, is that a protracted global recession will make life more difficult for Australia and will likely warrant a further policy response from government.

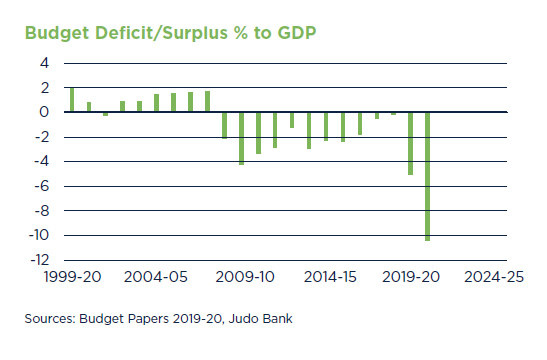

The Federal government postponed the release of its 2020-21 Budget until October. By then, the Government hopes to have a better handle on changes to tax revenue and spending. The small budget surpluses originally expected for 2019- 20 and 2020-21 will now become historically large deficits.

The level of government borrowing will rise substantially. However, the cost of servicing the debt – as a percentage of government revenue (approximately 6%) – will be comparable to that incurred during the 1990s recession (approximately 6%).

We can therefore assume, that this level of debt should pose no real challenge to our financial management capabilities, considering that the Government coped easily, with this level of debt repayment in the 1990s. Unlike the current health crisis, the debt burden, is NOT unprecedented.

Lesson Learnt #3:

Credit

During the Great Depression, the banking sector restricted credit to households and businesses. The banks had difficulty raising funds to onlend. Indeed, there were ‘runs’ on some banks as depositors scrambled for cash.

Today, Australian banks are stronger. Following the GFC they have been required to hold more capital. The banks also have access to further, cheap, capital if required.

This time round, banks can be part of the solution rather than part of the problem. This is an important and positive shift, both economically and culturally.

Lesson Learnt #4:

Social assistance

During the Great Depression there was no Federal government unemployment assistance. Any assistance given to the unemployed was State based and became known as sustenance or ‘the susso’. In today’s prices, the value of ‘the susso’ was around 25% of Centrelink unemployment benefits.

Today, the Federal government pays unemployment benefits, supports charities that provide social assistance and provides funding for Medicare.

The safety net for Australians is far better today than during the Great Depression. The purpose of the safety net, is to cushion the fall and add to overall demand in the economy. It is not designed however, to be at the forefront of economic recovery efforts.

Lesson Learnt #5:

Wages

Public service and many private sector wages were cut during the Great Depression. While this may have eased immediate pressure on government budgets and corporate cash flows, it reduced demand in the economy. Notably, the reductions of 1931 were reversed in 1934.

Australia still has National Wage Cases that determine minimum wage levels and yet, since 1991 wage determination has been at enterprise and individual levels. This has allowed far more flexibility within the economy and has been credited, in part, with the growth in the economy since the 1990s recession.

Lesson Learnt #6:

Moving with the times

Economies never stand still. Businesses change, products change, technology changes, attitudes change, services change, demographics change. The list is endless.

Next Steps

The Covid Economy

The longer the Covid-19 health related issues persist, the harder it will become to rebuild the economy. True, 90% of the economy may still be at work but the loss of 10% (or more) is both significant and serious.

We do not yet know, how the economies of other countries will cope. Will the US go into deep recession? Will China rebound? How exactly will Europe, Japan and the rest of Asia recover?

The picture painted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is not rosy. The IMF expect a 3% decline in global activity in 2020. This compares with the 0.9% decline that occurred after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008. The better news is that the IMF expects a pick up in 2021.

In the case of a full scale, extended global recession, the government may be called upon to take further action. The Australian dollar is likely to slide lower, interest rates will be lower for longer and the government may extend some of its various programs.

Reform and rebuild

In order to thrive amidst change, businesses, individuals and governments must adapt. As we progress towards recovery, managing constant change is the challenge. Adapting to the new normal, IS the new normal.

It is widely regarded that the current system of taxation in Australia is unsustainable. Individual income taxes are set to exceed 50% of tax revenue within the next few years.

Taxation of income is a disincentive to work. Taxation of profits is a disincentive to lift profits. Taxation of home sales is a disincentive to buy homes. Taxation on payrolls is a disincentive to employment.

If the ambition is to sustainably fund the demands for health, education, social assistance and many other worthy government services, we need to re-think the system.

Some general principles of taxation have been around for decades; namely efficiency, equity and simplicity. In the interests of a robust recovery, we need to add; clarity, sustainability and low compliance costs, to these fundamental principles.

Sadly, taxation in Australia doesn’t tick all of those boxes. There is substantial room for improvement. Hopefully the post Covid-19 political climate will also change, replacing head on confrontation amongst key stakeholders, with real, constructive negotiation.

As a society, we are capable of driving significant change. To thrive over the next decade, we will need to re-think our once seemingly intransigent economic, political and cultural ideologies.

Today, our collective focus is to journey out of the intense crisis management phase. As we welcome the gradual unwinding of ‘lockdown’ rules, we must continue to remain focussed on maintaining our ‘social distance’, staying in touch with our employees, and communicating with our customers, suppliers, creditors and our bankers. We will also need to navigate the process of unwinding the assistance programs, established in recent weeks.

Interest rates

The RBA’s cash rate was lowered to 0.25% in March. At the same time, the RBA announced that it would target a rate of 0.25% for threeyear bond yields.

With inflation historically low and some difficult times ahead for the economy – both in Australia and overseas – the cash rate seems likely to be on hold for several years. A return to 0.50% cash rate will signal the worst is behind us.

Likewise, the longer end of the yield curve is unlikely to see any substantial increases, while the US and European economies struggle with that fallout from Covid-19.

In summary, rates across all time frames will be lower for longer. Good for borrowers, not so good for depositors.

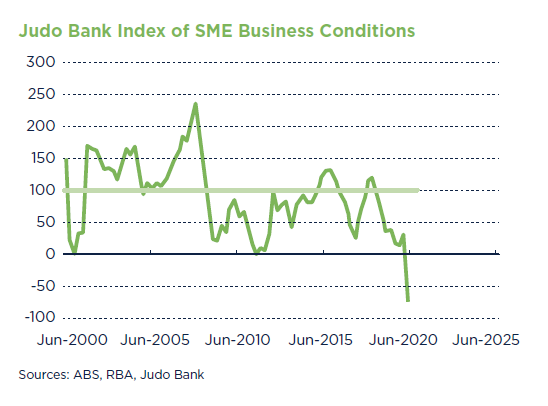

Judo Bank Index of SME Business Conditions

These are the most difficult circumstances to confront SME businesses, in recent memory. The Judo Bank index* of small business conditions, has fallen to its lowest level since tracking began in 1986. The decline in SME business conditions, is worse than the 1990s recession, where the unemployment rate exceeded 10%.

In the latest reading, the index fell sharply due to the massive drop in employment seen in late March/early April 2020. However, the impact of the fall in employment was partially offset by a solid rise in retail spending, as consumers scrambled for ‘lockdown essentials’. The rise in business credit over the same period, as businesses sought extra funds to assist them through the Covid-19 crisis, also contributed to the offset.

For those who like to crunch numbers and track the economy, the ABS in conjunction with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is putting out new, timely information on retail spending, employment, hours worked, trade, overseas students and business expectations and impacts. These reports will track the decline in activity and in time, demonstrate the recovery of the economy, beyond Covid-19.

*Judo Bank utilises a custom, data based, economic modelling tool, referred to as ‘The Index’. The Index sources data from the ABS and Reserve Bank of Australia, dating back to 1986. For more information re the construction of the index, refer to our SMEconomics Report #2.

Disclaimer

This document has been prepared by Judo Bank Pty Ltd ABN 11 615 995 581 AFSL 501091 (“Judo Bank”). Any advice contained in this document has been prepared without taking into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on any advice in this document, Judo Bank recommends that you consider whether the advice is appropriate for your circumstances.

So far as laws and regulatory requirements permit, Judo Bank, its related companies, associated entities and any officer, employee, agent, adviser or contractor thereof (the “Judo Bank Group”) does not warrant or represent that the information, recommendations, opinions or conclusions contained in this document (“Information”) is accurate, reliable, complete or current. The Information is indicative and prepared for information purposes only and does not purport to contain all matters relevant to any particular investment or financial instrument. The Information is not intended to be relied upon and in all cases anyone proposing to use the Information should independently verify and check its accuracy, completeness, reliability and suitability and obtain appropriate professional advice. The Information is not intended to create any legal or fiduciary relationship and nothing contained in this document will be considered an invitation to engage in business, a recommendation, guidance, invitation, inducement, proposal, advice or solicitation to provide investment, financial or banking services or an invitation to engage in business or invest, buy, sell or deal in any securities or other financial instruments.

The Information is subject to change without notice, but the Judo Bank Group shall not be under any duty to update or correct it. All statements as to future matters are not guaranteed to be accurate and any statements as to past performance do not represent future performance.

Subject to any terms implied by law and which cannot be excluded, the Judo Bank Group shall not be liable for any errors, omissions, defects or misrepresentations in the Information (including by reasons of negligence, negligent misstatement or otherwise) or for any loss or damage (whether direct or indirect) suffered by persons who use or rely on the Information. If any law prohibits the exclusion of such liability, the Judo Bank Group limits its liability to the re-supply of the Information, provided that such limitation is permitted by law and is fair and reasonable.

This document is intended only for clients of the Judo Bank Group, and brokers who refer customers to the Judo Bank Group, and may not be reproduced or distributed without the consent of Judo Bank.

The Information is governed by, and is to be construed in accordance with, the laws in force in the State of Victoria, Australia.